Working with violence and abuse in relationships

Working with families who are experiencing separation can raise issues around violence and abuse. As a professional working with these families, you have a responsibility to identify any risk in order to be able to offer the most suitable interventions.

For many years, it has been considered difficult or impossible to assist separated or separating parents to collaborate around their children's needs. One of the concerns that is often raised is that it puts separating parents (most often mothers) at risk of harm.

Sometimes, violence or abuse has been present throughout the relationship, and there is clear evidence that the risk of harm to both mothers and fathers, and their children, does rise during the separation process and afterwards as a result of the emotional and psychological pressures that parents are under.

It is critical that those parents who are at risk from coercive, controlling violence and abuse are recognised and signposted to the appropriate support services. However, it is also important that those parents who have found themselves in confrontational situations as a result of the separation are supported to manage their behaviours in ways that prevent further incidents.

Who does what to who?

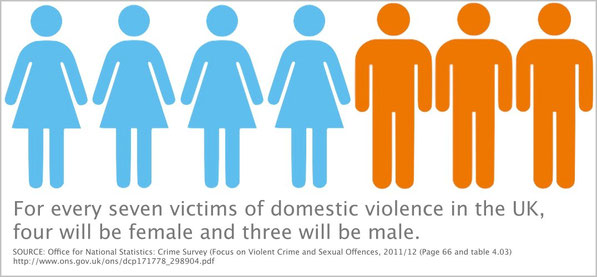

It is commonly assumed that violence and abuse in relationships is carried out by men against women. However, the statistics show that violence and abuse in relationships is also carried out by women against men.

Government figures show that:

- 40% of domestic abuse victims are male.*

- 7% of women and 5% of men were estimated to have experienced domestic abuse in the last year.*

- 1.1% of men and 1.3% of women were victims of severe force at the hands of their partner during 2011/12.**

Office for National Statistics: Crime Survey (Focus on Violent Crime and Sexual Offences, 2011/12)* Page 62 ** Table 4.01

Evidence from Australia found that 65% of women and 55% of men reported that they had experienced assaults against them by their former partner either during the relationship or after separation. [Australian Institute of Family Studies, Grania Sheehan and Bruce Smyth, ‘Spousal Violence and Post-separation Financial Outcomes’ (2000) 14 Australian Journal of Family Law 102]

The evidence that violence within relationships is nuanced and may have multiple causes and effects is not supported by the majority of UK women’s Domestic Violence organisations and advocates who tend to consider that it is ‘a consequence of the inequalities between men and women, rooted in patriarchal traditions that encourage men to believe they are entitled to power and control over their partners’. [Women's Aid briefing - perpetrator work in the UK 07.06.07]

Nevertheless, ‘a growing body of empirical research has demonstrated that intimate partner violence is not a unitary phenomenon and that types of domestic violence can be differentiated with respect to partner dynamics, context, and consequences’. [Differentiation among types of intimate partner violence: research update and implications for interventions. Joan B. Kelly Michael P. Johnson, Family Court Review 2008.]

It has been argued that ‘the patriarchy, power and control analysis remains more or less intact despite its incompatibility with emerging findings about domestic abuse’, [Beyond violence: Breaking cycles of domestic abuse, Dr Elly Farmer and Dr Samantha Callan, Centre for Social Justice, 2012] but that ‘it is no longer scientifically or ethically acceptable to speak of domestic violence without specifying, loudly and clearly, the type of violence to which we refer’ Johnson 2005, quoted in Different types of intimate partner violence, Dr Jane Wangmann, Australian Domestic & Family Violence Clearinghouse, 2011]

Using a triage approach

Using a triage approach, that differentiates between different types of violence and abuse, provides a framework for risk diagnosis, ensuring that the right interventions can be offered. The differentiation model protects vulnerable parents but explores the possibility of collaboration where there is no danger. Using a triage approach:

- helps parents to identify whether they are or have been in an abusive or violent relationship

- helps parents to assess whether collaboration is possible

- promotes collaboration where it is safe to do so

- does not not promote collaboration where it is not safe to do so

This differentiation approach separates out the risk of relationship violence and abuse in the following four categories:

Coercive Controlling violence and abuse

Coercive Controlling violence and abuse occurs when one parent controls the other through fear, physical harm, mental and emotional harm and psychological threat. There is a clear power imbalance in the relationship. It is often very difficult for an individual to escape this kind of abuse because it leaves them feeling scared for their well being if they take any action. Parents experiencing this type of violence or abuse must be immediately signposted to an appropriate, specialist support service.

Situational Couple violence and abuse

Situational Couple violence and abuse occurs as fights between couples where both are involved. It may be recurring or 'one off' in nature and causes shame and embarrassment. Usually, both parties are keen to work on behaviours. Parents experiencing situational couple violence will not present as being afraid or controlled and will be able to consider the different choices that they can make within the situation that they find themselves.

Separation Instigated violence and abuse

Separation Instigated violence and abuse occurs at the end of a relationship. Whilst it may cause distress, the parent does not feel controlled. It often involves violence on the part of both parents, both physical and verbal fighting, and parents will often feel ashamed and uncomfortable. Parents who present in this way are in need of support to understand the ways in which they can stop or prevent a reoccurrence of the violence.

Violent Resistance

Violent resistance is the use of violence to resist a violent or coercively controlling partner. It may be almost automatic and surfaces almost as soon as the coercively controlling and violent partner begins to use physical violence. It often makes matters worse and increases the levels of violence suffered.

Family Violence Differentiation in practice

An experienced professional will often be alert to the signs that violence or abuse is, or has been, present in a relationship and it is not unusual for a parent to reveal it in conversation. Where the situation is unclear, you may feel that gentle questioning as to whether any confrontations, violence or abuse is, or has been, present in the relationship is appropriate.

Where confrontations, violence or abuse are identified as being present, empathic questioning will provide the information required to assess the potential risks and allow the parent to reflect on their own individual situation. Example questions might include:

- Have there been arguments or fights in your relationship? Was that always the case or have things become worse as you separated?

- Would you say that both of you have been involved in any fights or has one of you usually been the person who started things?

- Tell me a little more about your fights? How bad would you say it gets?

- Have either of you threatened to physically hurt each other? Have either of you threatened to hurt the children?

- Would you say that either of you is afraid of the other? Are your children afraid of either of you?

- Have either of you made it difficult for the other to see their family or friends, have you felt like isolating your partner or been made to feel isolated in your relationship?

- Has either of you checked up on the other by text or by checking each other's mobile phone or the mileage on the car. Do you feel that either of you are excessively suspicious or jealous?

- Do either of you put the other one down, call each other names, ridicule each other in front of other people? Is this a regular part of your relationship which doesn't stop even if you ask for it to?

- Have either of you kept the other short of money so that you are unable to buy food for yourself or the children?

By matching up the information that a parent gives you with your understanding of the different categories of family violence and abuse, it is possible to ensure that vulnerable parents are protected, whilst ensuring that those parents who are not at risk are able to learn different behaviours to manage potentially confrontational situations, and collaborate around their children's needs.

Use your professional experience to triage parents using the following grid:

| Green | No violence or abuse present |

No barriers to collaboration: proceed without caution |

| Amber |

Situational Couple violence and abuse or Separation Instigated violence and abuse |

Potential barriers to collaboration: proceed with caution and explore situation management |

| Red |

Coercive Controlling violence and abuse or Violent Resistance |

Collaboration not possible: signpost to specialist services |

Further reading

Differentiation among types of intimate partner violence: research update and implications for interventions by Joan B. Kelly and Michael P. Johnson.

A growing body of empirical research has demonstrated that intimate partner violence is not a unitary phenomenon and that types of domestic violence can be differentiated with respect to partner dynamics, context, and consequences.

What's wrong with the Duluth Model?

Many Intimate Partner Violence treatment programs around the world, not least in the UK, are adopting the Duluth model, created by the Duluth, Minnesota Domestic Abuse Intervention Project. One of the most well known UK programmes following this model is the Freedom Programme created Pat Craven, which many practitioners consider to be extremely problematic and harmful.

Focus on: Violent Crime and SexualOffences, 2011/12

This release, the successor to ‘Homicides, Firearm Offences and Intimate Violence 2010/11: Supplementary Volume 2 to Crime in England and Wales 2010/11’ (Smith et al., 2012) is a collaboration between ONS and Home Office analysts. It explores a variety of official statistics on violence, and is primarily based on crimes recorded by the police in the year to March 2012 and interviews carried out over the same period on the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW).